Remember: you can connect your AI copilot to Zato documentation for real-time, accurate answers throughout this tutorial.

A starting Docker container with Zato expects for your project to be of a specific structure, which looks like this in the demo repository.

.

└── myproject

├── config

│ ├── enmasse

│ │ └── enmasse.yaml

│ ├── python-reqs

│ │ └── requirements.txt

│ └── user-conf

│ └── myconf.ini

└── impl

├── scripts

│ └── run-container.sh

└── src

└── api

├── billing.py

└── employee.py

Most of that structure is optional and whether you use a given element depends on the requirements of your project. So let's discuss it all in details.

The demo project comes with a script that does all the heavy lifting of starting and configuring a container.

It's under myproject/impl/scripts/run-container.sh and it's meant to be a blueprint for your own provisioning scripts, so feel free to modify it to suit your needs once you've completed this tutorial.

Make sure that you don't have other containers with Zato running, and then go ahead and run this script. It will start a new environment for you.

Most of this script is reusable across any kind of project, and you won't have to modify it a lot.

Let's check it closer now.

#!/bin/bash

# Common options

set -e

set -x

set -o pipefail

shopt -s compat31

# Find our current directory

CURDIR="${BASH_SOURCE[0]}";RL="readlink";([[ `uname -s`=='Darwin' ]] || RL="$RL -f")

while([ -h "${CURDIR}" ]) do CURDIR=`$RL "${CURDIR}"`; done

N="/dev/null";pushd .>$N;cd `dirname ${CURDIR}`>$N;CURDIR=`pwd`;popd>$N

# What environment this is

export env_name=myproject

# What password to use when logging in to the dashboard

export dashboard_password=${My_Password:-$(uuidgen)}

# What Zato version to use

export zato_version=4.1

# Name the container

export container_name=zato-$env_name

# Absolute path to where to install code in the container

export target=/opt/hot-deploy

# Full address of the remote Docker package

export package_address=ghcr.io/zatosource/zato-$zato_version:latest

# Absolute path to our source code on host

export host_root_dir=`readlink -f $CURDIR/../../`

# Directory on host pointing to the git clone with our project

export zato_project_root=$host_root_dir

# Our enmasse file to use

export enmasse_file=enmasse.yaml

export enmasse_file_full_path=$host_root_dir/config/enmasse/$enmasse_file

# Directory for auto-generated environment variables

mkdir -p $host_root_dir/config/auto-generated

# Populate environment variables for the server

echo '[env]' > $host_root_dir/config/auto-generated/env.ini

echo My_API_Password_1=$My_API_Password_1 >> $host_root_dir/config/auto-generated/env.ini

echo My_API_Password_2=$My_API_Password_2 >> $host_root_dir/config/auto-generated/env.ini

echo Zato_Project_Root=$target/$env_name >> $host_root_dir/config/auto-generated/env.ini

# Log what we're about to do

echo Starting container $container_name

docker rm --force $container_name &&

docker run \

\

--name $container_name \

--restart unless-stopped \

\

-p 22022:22 \

-p 8183:8183 \

-p 17010:17010 \

\

-e Zato_Dashboard_Password=$dashboard_password \

-e Zato_Log_Env_Details=true \

\

--mount type=bind,source=$zato_project_root,target=$target/$env_name,readonly \

--mount type=bind,source=$enmasse_file_full_path,target=$target/enmasse/enmasse.yaml,readonly \

--mount type=bind,source=$host_root_dir/config/auto-generated/env.ini,target=$target/enmasse/env.ini,readonly \

--mount type=bind,source=$host_root_dir/config/python-reqs/requirements.txt,target=$target/python-reqs/requirements.txt,readonly \

$package_address

The most important lines:

Line 15 - gives your environment a name, but observe that it must be the same as the name of the top-level directory of your project (here: myproject), so you need keep the two in sync.

Line 18 - set a password to log in to your Dashboard with (http://localhost:8183, user: admin). This password will be likely read from your host's environment variables but you can as well pull it from any other place, e.g. AWS Secrets Manager.

Lines 46-49 - exports environment variables for the server to use. This is how you pass passwords and credentials from your host to the container (more about it below).

Lines 67-70 - mount all the project directories from the host to /opt/hot-deploy inside the container.

In your own projects - you can leave the whole script untouched except for lines 15, 18, and the environment variables. The rest can stay as it is.

Remember - this script is a good template, but if you prefer to achieve the same using Docker Compose or other tools, that's fine as well, as long as you map the correct directories and provide the expected variables.

Your code goes to a directory called src. You need to use that name, otherwise your code will not be picked up by the server.

Inside that directory, you can have a flat list of Python files with Zato services, or you can create a tree of directories with Python files, like in a regular Python project, but they always must be under the "src" path.

No matter if it's a flat list of files, or directories with subdirectories and so on, they must be contained within directories that start with the names listed below. Otherwise, the starting server won't pick them up and your code won't be deployed.

# A flat list of Python files

.

└── myproject

└── impl

└── src

└── api # Matches prefix "api" (exact match)

├── billing.py

└── employee.py

# Two flat lists of Python files

.

└── myproject

└── impl

└── src

└── api_internal # Matches prefix "api"

│ ├── billing.py

│ └── employee.py

└── adapter_external # Matches prefix "adapter"

├── crm.py

└── training.py

# A tree of directories with Python files

.

└── myproject

└── impl

└── src

├── api # Matches prefix "api" (exact match)

│ └── dataverse

│ └── invoices.py

│ └── payments.py

├── channel_events # Matches prefix "channel"

│ └── jira

│ └── hr.py

│ └── onboarding.py

└── core_integrations # Matches prefix "core"

└── salesforce

└── partners

└── crm.py

└── batch.py

In other words, you can use any files and any directories for your own code, but they all must be within the directories whose names match the prefixes listed above, because in this way Zato understands that this is not just any Python code, but your services that have to be deployed.

Remember to add the __init__.py files if you decide to use nested directories - just as you would do it in any Python library with subdirectories.

Finally, "myproject" is just a name of the top-level directory, so you'll probably change it to the name of your company, but when you do it, make sure to change it in the provisioning script too (line 15 in the provisioning script).

An enmasse file is a YAML representation of configuration that you create in the Zato dashboard.

Each entry in an enmasse file represents an object that you want to create. For instance, to create a REST channel, you write this:

channel_rest:

- name: "api.dataverse.invoice.get"

service: "mycompany.dataverse.invoices.get-invoice"

url_path: "/api/dataverse/invoice/get"

When a Docker container starts, it tries to read a file with such entries from /opt/hot-deploy/enmasse/enmasse.yaml inside the container. If you place anything there (and the blueprint script does), the server will read it and everything from that file will be imported. If the file doesn't exist, nothing is imported.

The idea is that your team keeps adding more and more entries to this file over time, with each new project. Because the files are self-explanatory, everyone will learn how to do it in no time.

Using enmasse, you can import your configuration in new containers, and in this way your builds, your environments, will be reproducible

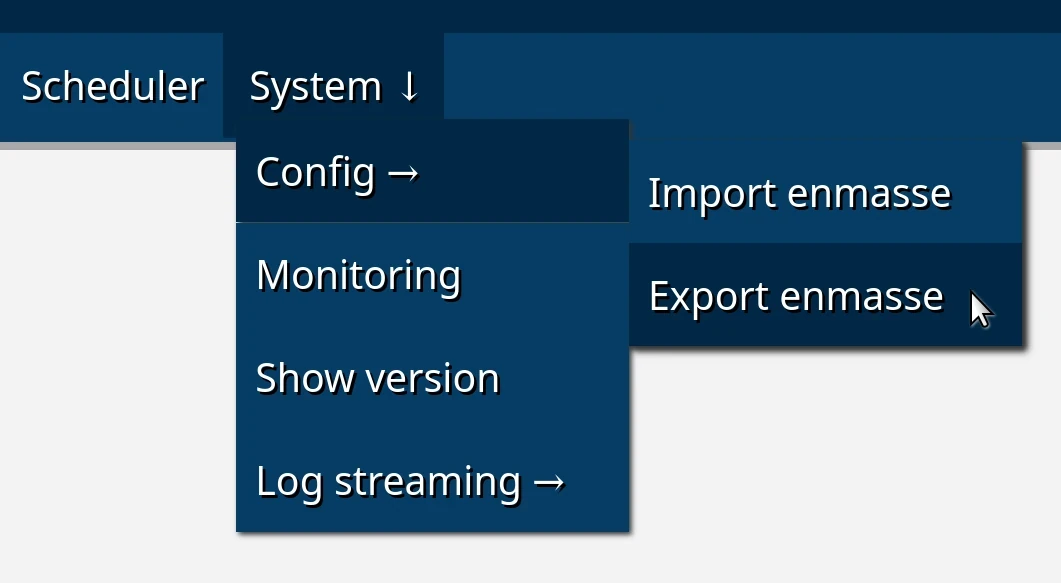

A question you may be asking is: "Great, I have this sample enmasse file from your blueprint repo, but how do I create one myself?", and there are two ways.

You'll often come across situations where an object will depend on a security definition.

For instance, you'll have a security definition called "HR API Key", and you'll have two REST channels that make use of the same credentials, from that security definition.

In such a case, refer to that security definition by its name, as below:

security:

- name: "HR API Key"

username: hr

password: Zato_Enmasse_Env.My_API_Password_1

type: basic_auth

realm: MyProject

channel_rest:

- name: api.dataverse.invoice.get

service: mycompany.myapi.billing.get-invoice

url_path: /api/billing/invoice/get

data_format: json

security_name: "HR API Key"

And this brings us to the question of how and where to keep passwords and other credentials, so let's talk about that now.

You certainly don't want to commit passwords, or any credentials, to your git repository, so the question arises, how can enmasse make use of them? For instance, when it creates a security definition, how does it know what password to use?

The easiest way to pass passwords to enmasse is to use environment variables. Any value in an enmasse file can be read from the server's environment by prefixing it with Zato_Enmasse_Env. - that's the indicator, not the "$" dollar sign.

For instance, password: "Zato_Enmasse_Env.My_API_Password_1" will look up an environment key called "My_API_Password_1" when the server is starting and enmasse runs.

But how do you pass environment variables to the container from your host? That's what lines 46-49 do in the sample provisioning script. Inside the container, they create a file called /opt/hot-deploy/config/auto-generated/env.ini which is what a starting server will try to read. If it finds this file, all the entries will be environment variables that enmasse can use.

To add a dependency from PyPI to your project, add it to config/python-reqs/requirements.txt. It's a regular Python requirements file, the same that the Python's pip command uses, so you add one requirement per line.

For instance, let's say we need to work with Azure Blob files and you'd also like to have a nice way to convert XML into Python dicts. Here's what you'd add to the file:

Zato lets you keep your own custom configuration for super-fast retrieval directly from RAM, with zero network overhead.

You do it my creating .ini files in the config/user-conf directory.

In runtime, the contents of any .ini file from this directory is available to your services via self.config. Let's analyze an example.

Let's say we have a file called myproject/config/user-conf/myproject.ini, with these entries:

def handle(self):

# Will print "Type 1"

self.logger.info('First type is: %s', self.config.myproject.employee.type1)

# Will print "Type 2"

self.logger.info('Second type is: %s', self.config.myproject.employee.type2)

# Will print "Group 1"

self.logger.info('First group is: %s', self.config.myproject.employee.group.group1)

# Will print "Group 2"

self.logger.info('Second group is: %s', self.config.myproject.employee.group.group2)

A great thing about such configuration files is that they are very, very fast to read in runtime. When the server starts, it reads the whole file and then you access it straight from RAM, so there's virtually zero overhead of using them, and yet they offer a very clean way to keep your configuration separate from code.

Your rule engine config files also go to the same config/user-conf directory, e.g. you'll create a file like config/user-conf/crm.zconf for your CRM-related rules. Follow this link to read more about the rule engine built into Zato.

/opt/hot-deploy/startup.sh| Use case | Description |

|---|---|

| Installing system packages | Download or install additional packages that your services require, e.g. HashiCorp Terraform or any other |

| Third-party agent installation | Install and configure APM agents like Datadog, New Relic, or Dynatrace for monitoring |

| Monitoring integration | Invoke your monitoring endpoints to signal that a Zato container is starting |

| Dynamic secret retrieval | Fetch credentials from Azure Key Vault, HashiCorp Vault or AWS Secrets Manager at container start time |

| Compliance auditing | Log container startup events to your SIEM system with full context about version, configuration, and environment |

| Dependency health checks | Verify that required databases, message queues, and external APIs are reachable before the server starts |

| Custom firewall rules | Configure ufw rules for container-specific network policies |

| Configuring system settings | Set up system permissions, kernel parameters, or other OS-level configuration |

Example startup script:

So that's how you deploy your Zato projects and solutions: